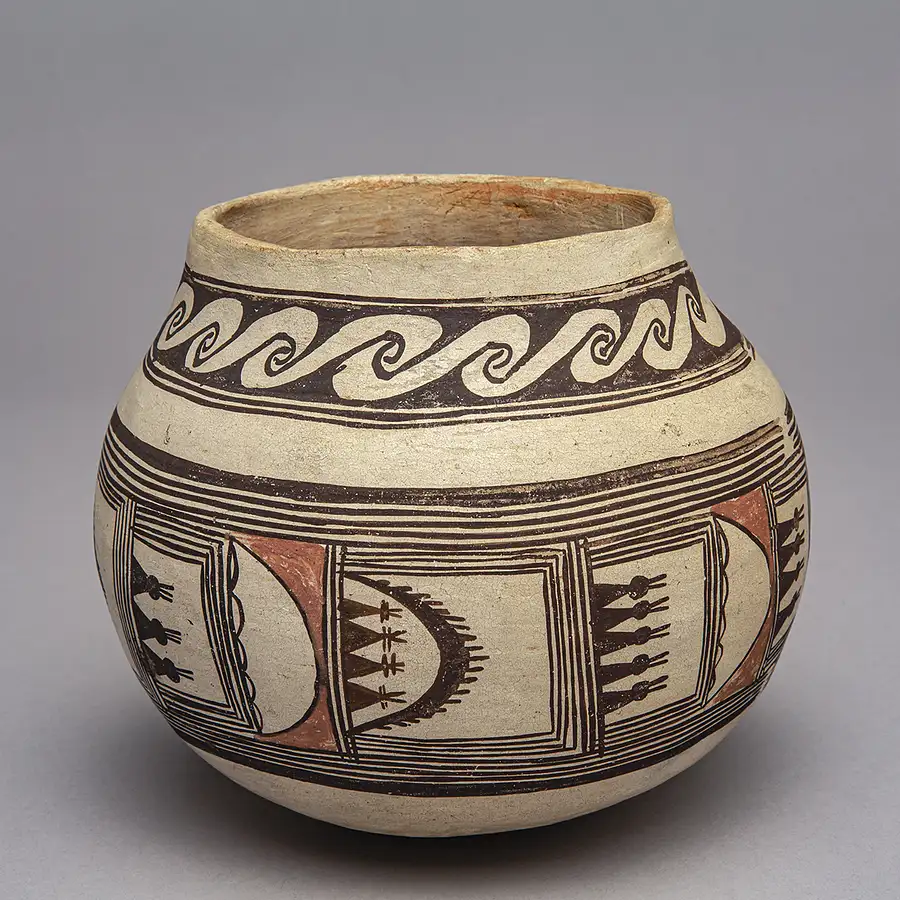

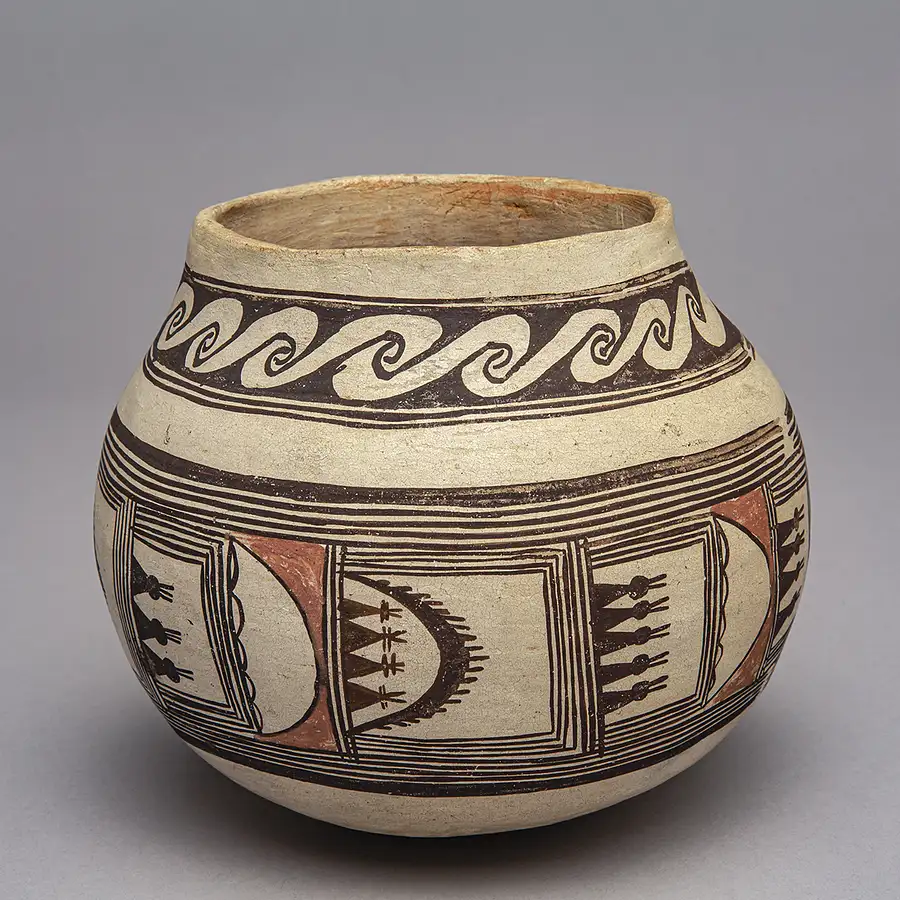

Date of production: Around 1890–95

Acquisition: In 1895 from Abraham Spiegelberg, Santa Fé

Acquisition by the museum: donated in 1902 by Aby Warburg

Probably from San Ildefonso, New Mexico, USA

Painted clay

undocumented

Ø 31.2 cm, H 31 cm

B 6098

Would you like to submit a comment or other contribution regarding this story?

You can write to us and/or upload pictures, films or sound files. Here´s the form, just click on the button below and be part of tell me!

tell me