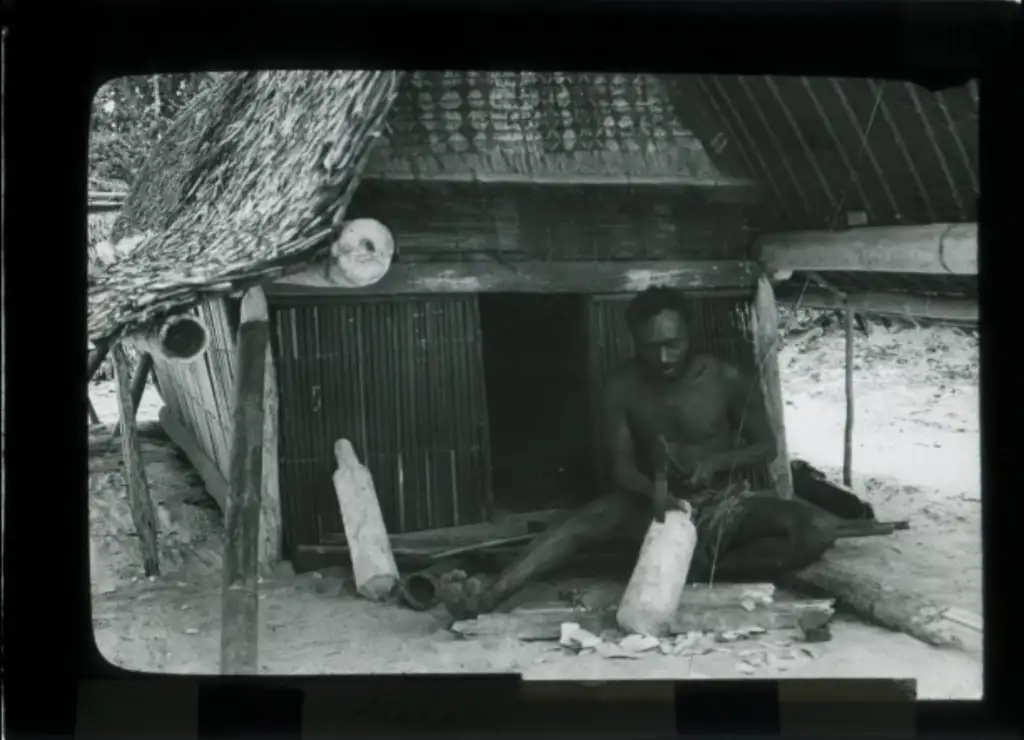

Boat ornament for a Malagan celebration. The artist's name is not on the museum archives' inventory card.

Date of production: Second half of the 19th century.

Acquisition by museum: gifted by Ruben Jonas Robertson in November 1884

New Ireland, Papua New Guinea

Wood, paint

undocumented

W 43 cm, D 14 cm, H 29 cm

E 871

.jpg?locale=en)

Would you like to submit a comment or other contribution regarding this story?

You can write to us and/or upload pictures, films or sound files. Here´s the form, just click on the button below and be part of tell me!

tell me